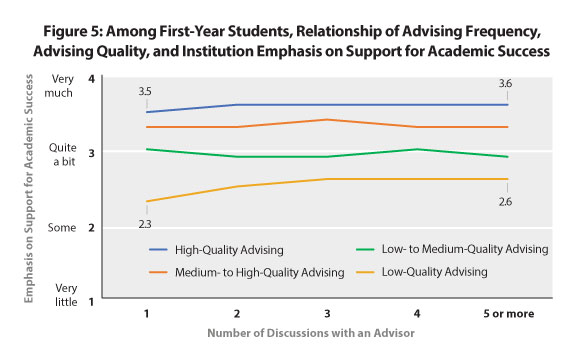

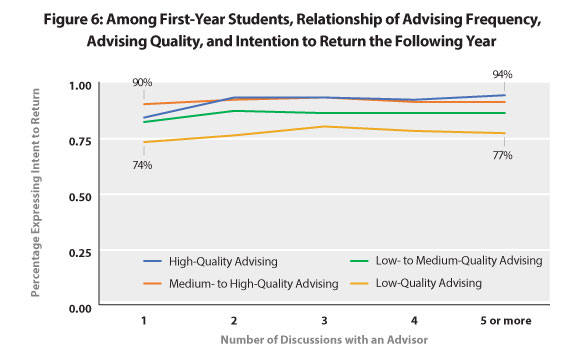

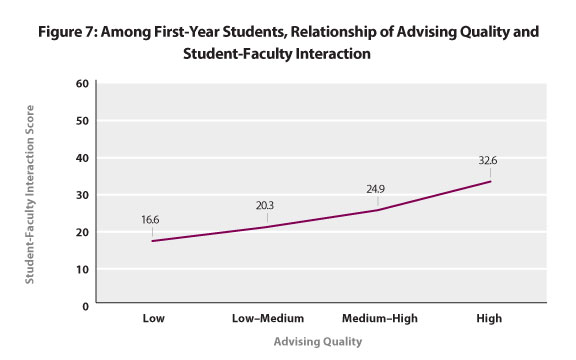

The advising needs of new students differ from the emphasis on graduation and post-college planning for seniors, but interactions with advisors and the quality of the advising experience are important for all students. The analyses below examine two characteristics of advising—the number of times a student discussed academic interests, course selections, or academic performance with an advisor and the quality of those advising experiences–among 10,000 first-year students and nearly 15,000 seniors at 55 US and two Canadian institutions.

Academic Advising: Quality Matters More Than Quantity

Frequency of Discussion About Academic Matters

It is generally recommended that students meet with their advisor at least once per semester. It is thus unsurprising that only 3% of first-year students and 6% of seniors never discussed their academic interests, course selections, or academic performance with an academic advisor, faculty member, or a success or academic coach (hereafter collectively referred to as advisor) during the 2018–19 school year. Indeed, more than half of both first-year students and seniors had five or more such meetings (Table 1).

Table 1: Number of Times Students Discussed Their Academic Interests, Course Selections, or Academic Performance with an Advisor

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 or more | |

| First-year students | 3% | 6% | 11% | 11% | 13% | 56% |

| Seniors | 6% | 7% | 11% | 10% | 13% | 53% |

Advising Quality

NSSE’s Topical Module on Academic Advising includes 10 questions regarding students’ experiences with an advisor, including how much an advisor was available when needed, provided prompt and accurate information, and actively listened to student concerns. We combined these responses for an overall measure of advising quality, and then grouped the scores into four categories ranging from low to high (Table 2).

Table 2: Quality of Academic Advising

| Low | Low-Medium | Medium-High | High | |

| First-year students | 11% | 38% | 38% | 14% |

| Seniors | 15% | 36% | 34% | 15% |

Note: Scores were computed for students who responded “Very little” to “Very much” (excluding “Not applicable”) on at least six of the 10 items. Students who had no advising meetings were excluded. The 10 items representing advising quality are from question 3 of NSSE’s Topical Module on Academic Advising: nsse.indiana.edu/pdf/NSSE_2020_Academic_Advising_Module.pdf