Sadly, many college students fail to complete their degrees. For example, only 60% of students entering a bachelor’s degree-granting institution earn a degree within six years (U.S. Department of Education, 2018). Compared to graduates, students who drop out tend to earn less, are more likely to default on student loans, and have lower life satisfaction on average. Low degree-completion rates are also costly to institutions that invested in students through financial aid and other forms of subsidy, and must recruit new students to replace those who leave. Because colleges and universities can stem the tide of student attrition by emphasizing aspects of the student experience that matter to retention, we examined the relationship between engagement in the first year and a student’s likelihood of returning to campus the following fall term.

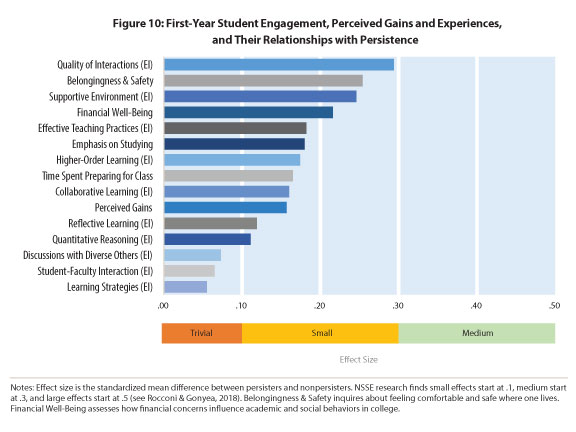

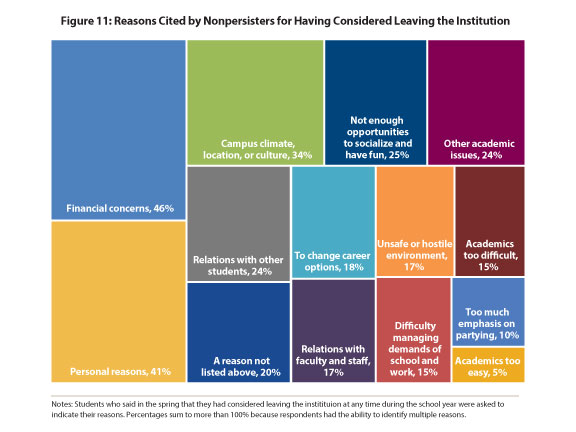

We obtained student-level persistence data (spring 2018 to fall 2018) for a sample of first-year students from 75 institutions that participated in a study funded by the ACUHO-I Research and Education Foundation examining students’ living arrangements. These institutions were diverse in terms of size, sector, student body, and Carnegie Classification, reflecting the diversity of four-year public and private, not-for-profit institutions nationally. Institutional persistence rates ranged from 53% to 98%, with a median of 92%. (These persistence rates are higher than what is typically reported because they focus on spring to fall, not fall to fall, persistence.) We compared persisters and nonpersisters on NSSE Engagement Indicators (EIs; see pp. 14–15), two key academic challenge items, and two factors from the living arrangements study.

Since 2018, The University of Tampa (UT) has aimed a laser-like focus on raising the first-year student retention rate. This campaign inspires all campus units to identify how they influence retention and where opportunities for improvement exist, and then to work collaboratively to plan, implement, and assess retention efforts. A key aspect of UT’s approach was a deeper dive into data from the perspectives of academic and student affairs and multiple years of NSSE data. Motivation for improvement came from a first-year retention rate 3 to 4 points lower than that of peer institutions. NSSE results provided nuance, for example, demonstrating UT’s strengths in student-faculty interaction and students’ dedication of time to co-curricular activities and community service. NSSE also pointed to areas for improvement such as support for learning and interactions among students, faculty, and administrators.

Since 2018, The University of Tampa (UT) has aimed a laser-like focus on raising the first-year student retention rate. This campaign inspires all campus units to identify how they influence retention and where opportunities for improvement exist, and then to work collaboratively to plan, implement, and assess retention efforts. A key aspect of UT’s approach was a deeper dive into data from the perspectives of academic and student affairs and multiple years of NSSE data. Motivation for improvement came from a first-year retention rate 3 to 4 points lower than that of peer institutions. NSSE results provided nuance, for example, demonstrating UT’s strengths in student-faculty interaction and students’ dedication of time to co-curricular activities and community service. NSSE also pointed to areas for improvement such as support for learning and interactions among students, faculty, and administrators.